1. Russia Post War

I listened to a podcast with a US former Supreme Commander of NATO, I think that was his title. Remarkably, he said that the West was afraid that Ukraine would win the war. The complicating factor is a defeated Russia post war: the Russian army is failing but his war of intimidating Western leaders is succeeding. So, the problem might be that Russia will implode if they lose or Putin will be backed into using nuclear weapons. Hmmm.

Check out The Foreign Desk with Andrew Mueller.

2. Migrant Deaths in the Mediterranean

Migrant boat with hundreds of missing migrants—with some estimates at 500 missing and presumed drowned—last week could be the worst ever in the Mediterranean. And that is saying something given all the tragedies and suffering of over the past ten plus years. With smuggling on the rise, and so many refugees on the run, as the survivors from this tragedy attest (survivors were all “boys and men from Egypt, Pakistan, Syria and the Palestinian territories”), what has to be done? One of the many, many issues that deserves our attention is that most of the missing are women and children.

3. Sudan Peace Talks Adjourn

I am finding it more and more difficult to find words to talk about the War in Sudan, as once again the Janjaweed are committing ethnic cleaning in Darfur.

Yet peace talks are paused. Reuters reported that Molly Phee, US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs told a House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee said that the US adjourned the talks in Jeddah because: “because the format is not succeeding in the way that we want,” Both sides are still violating agreements and resumed fighting at the end of the last ceasefire.

US policy is to impose sanctions on companies fuelling the conflict. But with charges of genocide, what are we doing? More of this next week.

4. Rwandan Genocidaire Seeking Asylum in South Africa

Fulgence Kayishema was in court in Rwanda accused of ordering the deaths of 2000 Tutsi seeking refuge in a church during the 1994 Rwanda genocide. He was charged in 2001 and has been in hiding in South Africa ever since. Kayishema is seeking asylum in South Africa. Meanwhile, a few weeks ago, Felicien Kubuga, at 88 years of age, was ruled unfit to stand trial at The Hague. He has been accused of financing the genocide and using his radio station, Milles Collines, to foment hate.

I am reading a book by Michela Wrong, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and African Regime Gone Bad (New York: Public Affairs, 2021) that describes the government of Paul Kagame, in power since his political/military movement based in Uganda came to power in Rwanda post genocide; he has been in power ever since. According to Wrong, he has been ordering the deaths of his political rivals among other deeply troubling state sponsored violence aimed at maintaining his and his government’s power.

I am working on writing a longer piece on post genocide governing. Any suggestions on what I should read? Or be thinking about?

Many pundits will surely, and impetuously, speculate on the reasons. Impeachment. Distraction. Oil. Money. Power. Elections. US coverage will default along the rancor and unseemliness of the current state of the US political climate and culture. More sober analysis will await the foreign press or a few weeks after more details emerge and Iran’s response can be factored in.

Many pundits will surely, and impetuously, speculate on the reasons. Impeachment. Distraction. Oil. Money. Power. Elections. US coverage will default along the rancor and unseemliness of the current state of the US political climate and culture. More sober analysis will await the foreign press or a few weeks after more details emerge and Iran’s response can be factored in.

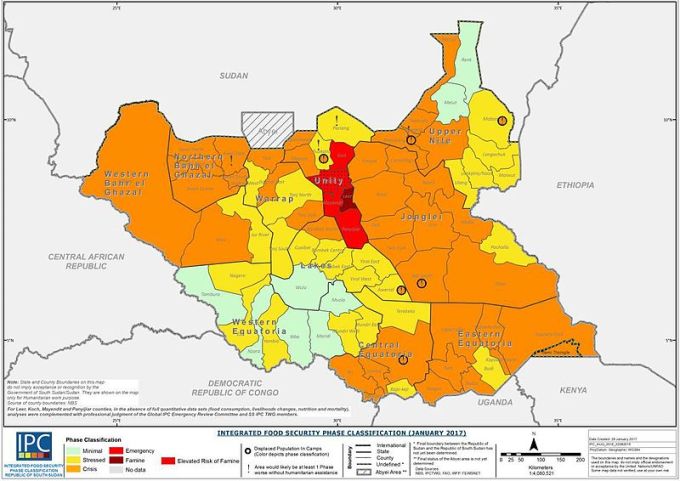

ood aid deliveries, which is, in part, why the UN’s announcement came with the warning that famine could easily spread beyond the 100,000 people currently affected. In total, nearly one million people living in the Unity state are at risk.

ood aid deliveries, which is, in part, why the UN’s announcement came with the warning that famine could easily spread beyond the 100,000 people currently affected. In total, nearly one million people living in the Unity state are at risk.

continued expansion of North Korea’s nuclear weapon capabilities will cost the average North Korean. If the past is truly a predictor of the future, we can expect to see an increase in the death of North Koreans from starvation and other effects of severe malnutrition; we could even see another famine like the country experienced throughout the 1990s, and near-famine in the late 2000s when food shortages were common.

continued expansion of North Korea’s nuclear weapon capabilities will cost the average North Korean. If the past is truly a predictor of the future, we can expect to see an increase in the death of North Koreans from starvation and other effects of severe malnutrition; we could even see another famine like the country experienced throughout the 1990s, and near-famine in the late 2000s when food shortages were common.